Slavery, segregation, genocide and apartheid. The cruelty that lies in the heart of man is perhaps one of histories worst kept secrets. Among death and taxes, the destruction of those who look,speak and act like us is one thing history has taught us is an inevitability.

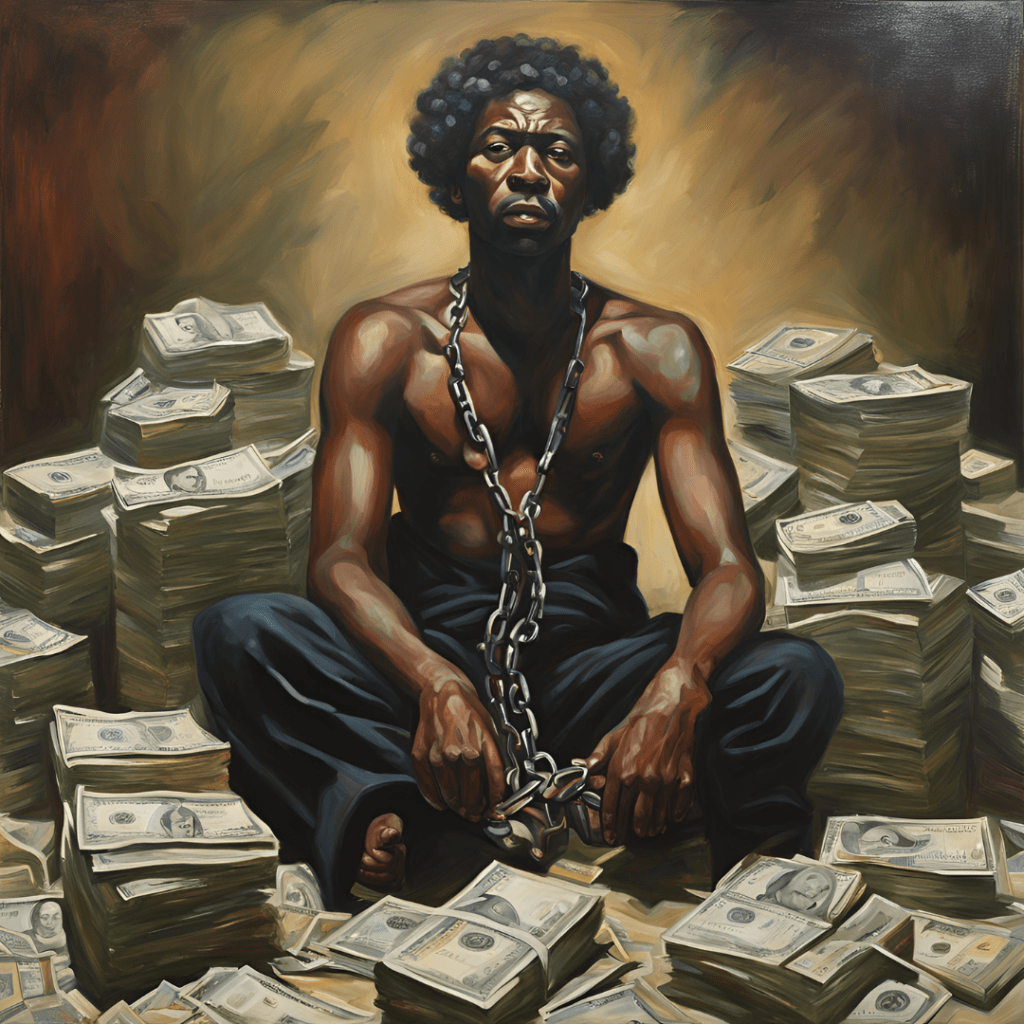

In a grim exploration of some of history’s most atrocious instances of organized violence against humanity, one must confront the unsettling reality that beneath the veil of ideological fervor or racial hatred, there often lies a cold, calculating calculus of economic gain. This analysis does not seek to excuse the inexcusable, but rather to unearth the material motivations that have driven societies to commit unspeakable acts. By dissecting the economic incentives and the structures of power that profit from human suffering, we gain a clearer, albeit more disturbing, understanding of how greed and the pursuit of wealth can fuel atrocities on a mass scale. This rationalization forces us to confront the uncomfortable truth that, in many cases, the engines of human destruction have been powered not merely by fanaticism, but by the ruthless logic of economic exploitation.

The Slave Trade

It is obviously not a conversation about colonial economics without mention of the notorious transatlantic slave trade. Many of us are obviously familiar with the atrocities and gruesome details of this era, however not so much the economics of it. Lets unpack.

According to the Gilder Lehrman institute of American Studies,” Over the period of the Atlantic Slave Trade, from approximately 1526 to 1867, some 12.5 million captured men, women, and children were put on ships in Africa, and 10.7 million arrived in the Americas. The Atlantic Slave Trade was likely the most costly in human life of all long-distance global migrations.”

Those 12.5 million people represent a profound loss of productivity, not just as a workforce but as potential innovators, artisans, and contributors to society. Each individual who was torn from their homeland and forced into slavery also represented the loss of countless possibilities—families that could have been built, communities that could have thrived, and economies that could have flourished in ways we can only imagine. The brutal reduction of these human beings to mere instruments of labor denied entire nations and continents the fruits of their intellect, creativity, and ambition.

In economic terms, the value of the labor stolen from these individuals, if we consider the equivalent wages of the time, could be estimated at around $8.1 billion in today’s money. Each enslaved person might have produced labor worth $650 over a lifetime, but this is only a fraction of the broader economic impact.

The wealth generated by their forced labor fueled European industrialization, with countries like Britain accumulating riches that would eventually drive the Industrial Revolution. This economic gain for Europe, potentially in the range of trillions when adjusted to current values, came at an incalculable cost to Africa. The continent not only lost the direct value of labor but also suffered severe disruptions to its economies, social structures, and long-term development. The true cost, both in human and economic terms, is immeasurable, and the legacy of this exploitation continues to shape global inequalities today.

Apartheid South Africa

Modern day South Africa is considered one of the most unequal societies in the world with the top 10% of the adult population owning nearly 86% of Aggregate wealth in the economy.

Well what does this look like from a demographic perspective?

The average black household in South Africa owns only about 5% of the wealth of the average white household in the country. A very clear and alarming disparity. What could have caused this?

Enter Apartheid South Africa, one the darkest eras in the country’s history which only came to an end in 1994. During this period of systemic discrimination and segregation, white South Africans were afforded privileges such as economic priority, social securtiy as well as the constitutional right to vote. Well what is the problem with this? None of these provisions were afford to the (majority) black populaton whom were not even allowed to share a bus with the white man.

To quantify the wealth accrued by white Afrikaners during apartheid in empirical dollar terms is a complex task due to the various forms of wealth generation and accumulation over several decades. However, significant economic benefits were realized through discriminatory policies that favored the white population at the expense of the Black majority.

- Land Ownership: By 1994, white Afrikaners, who made up only about 10% of the population, owned approximately 87% of the land in South Africa. This land was often the most fertile and resource-rich. The economic value of this land alone, given its agricultural potential and mineral wealth (including gold and diamonds), could be estimated in the tens of billions of dollars. For instance, the mining industry, which was a cornerstone of the South African economy, contributed significantly to the wealth of Afrikaners.

- Income Disparities: The apartheid system created and maintained vast income disparities. By the late 1980s, the average annual income for white households was about eight times higher than that of Black households. In 1980, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita for whites was approximately $12,000, compared to just $2,000 for non-whites. Considering that the white population was around 5 million, this disparity in income levels reflects significant economic accumulation among Afrikaners.

- Government Spending: During apartheid, government spending was heavily skewed towards the white population, with education, health, and infrastructure investments primarily benefiting them. This resulted in a significant buildup of human capital and physical infrastructure that further reinforced economic advantages for white Afrikaners.

- Corporate Wealth: Many large corporations that are still central to South Africa’s economy today, such as Anglo American and De Beers, benefited from the apartheid system. These companies were predominantly owned and managed by white Afrikaners and their wealth grew substantially during this period. The market capitalization and profits of these companies, especially in the mining sector, contributed to the wealth accumulation.

- Financial Instruments: Afrikaners also had privileged access to financial instruments like credit and investments, which allowed them to grow wealth through the stock market and other financial means. The Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) saw significant growth during apartheid, much of which benefited white-owned businesses and investors.

While exact figures are difficult to pin down, estimates suggest that the cumulative wealth generated and accrued by white Afrikaners through these means could be valued in the hundreds of billions of dollars when adjusted for inflation and current economic conditions. The lasting effects of this wealth accumulation continue to influence economic disparities in South Africa today.

Conclusion

As we dissect the economic underpinnings of slavery and apartheid, we begin to understand how these systems of oppression were rationalized and justified by those who stood to benefit. These were not mere acts of brutality born out of hatred alone; they were calculated, strategic endeavors designed to secure economic dominance and wealth. The transatlantic slave trade and apartheid were framed by their architects as necessary for the economic growth and prosperity of nations and a racial elite, turning human suffering into a means to an economic end.

The justification of these atrocities through economic gain reveals a cold and calculating logic that sought to mask the moral repugnance of these systems under the guise of economic necessity. By viewing human beings as mere commodities or obstacles to wealth, these systems created a framework where exploitation was not just tolerated but institutionalized.

Today, as we analyze the wealth and power accumulated during these dark periods, it becomes clear that the economic narratives crafted to support slavery and apartheid were not only powerful but also dangerously persuasive. They allowed entire societies to overlook the humanity of millions, reducing them to mere cogs in a vast economic machine. Understanding this is crucial, for it forces us to recognize the lengths to which those in power will go to maintain their economic interests, often at the expense of basic human rights and dignity.

This realization should serve as a sobering reminder of the need to critically examine the economic motivations behind modern-day inequalities and to ensure that history does not repeat itself in new forms.

Leave a comment