by leruo monang

“Aid has been, and continues to be, an unmitigated political, economic, and humanitarian disaster for most parts of the developing world.” Says Dambisa Moyo, award winning Zambian Economist and author of Dead Aid.

Moyo’s assertion challenges the widely held belief that foreign aid is a panacea for the economic struggles of the developing world. Instead, she argues that aid fosters a cycle of dependency, weakens local institutions, and perpetuates corruption. By providing a steady stream of external funds, governments are often incentivized to prioritize donor interests over domestic needs. This dynamic stifles innovation, discourages accountability, and hinders the development of sustainable economic systems. Moreover, the influx of aid can distort markets, suppress local entrepreneurship, and foster a culture of reliance, ultimately undermining the very growth it seeks to stimulate.

Critics of Moyo’s perspective, however, argue that aid, when strategically deployed, has the potential to address critical gaps in infrastructure, healthcare, and education. Success stories in countries that have used aid to improve literacy rates, combat diseases, and build essential infrastructure illustrate the nuanced role of foreign assistance. The real issue, they contend, lies in the implementation and governance of aid programs, rather than in the concept of aid itself. Moyo’s critique, while valid in many instances, calls for a reevaluation of aid frameworks to ensure they empower local economies and foster long-term self-reliance rather than perpetuate a cycle of dependency.

These critiques however assume benevolance on the part of both the donor and the custodians of the donation. It is perhaps the world’s worst kept secret that Africa has, for decades, been subject to some of the worst corruption we have ever seen. Scandals around state capture, embezzlement, money laundering and government kickbacks have plagued the continent since time immemorial. Moyo argues that the cash-flow from foreign not only facilitates corruption but incentivizes it.

The Proverbial Cookie Jar

Imagine you are the President of a fictional African nation. We will call her Rimbabwe. Rimbabwe has just come off the back of a devastating battle for independence from British colonial rule. The towns are in ruins, the people are destitute and the economy is in tatters. Infrastructural developments need to happen but there is no money to finance them.

Here comes the good Samaritan in the form of the World Bank, awarding you a relief loan of US$10 billion to rebuild. Keep in mind, Your Excellency, that there are no institutions to keep you accountable, no checks and balances to ensure the wise stewardship of these funds and no watch dogs breathing down your neck to prevent you from sticking your fingers in the cookie jar. Do you see where I am going with this?

The allocation of large sums of money to nations with underdeveloped institutions, gaps in legislation and an absence of accountability fosters corruption and encourages politics of the stomach. Those that aspire to reach positions of power for the sole purpose of state capture and feeding their individual desires.

The Fine Print: Ts and Cs of Foreign Aid

Foreign aid is often presented as an altruistic gesture, a lifeline extended to nations in need. Yet, beneath this benevolent facade lies a complex web of geopolitical interests. For many donor countries, aid serves as a strategic tool to exert influence over the political landscapes of recipient nations. By attaching conditions to financial assistance, western powers have often leveraged aid to dictate policy directions, sway election outcomes, and suppress dissent. In this dynamic, the true beneficiaries of aid are not the impoverished citizens of the Global South but the geopolitical agendas of those in the Global North. Aid often becomes a conduit for political manipulation, entrenching foreign dominance in domestic affairs under the guise of generosity.

Foreign aid is rarely given without conditions, and these conditions often infringe on the sovereignty of recipient nations. Whether through structural adjustment programs imposed by international financial institutions or bilateral agreements tied to political reforms, aid frequently requires recipients to align their policies with the interests of donor nations.

These conditionalities can force governments to adopt measures that may be economically or socially detrimental, such as privatizing public services, cutting subsidies, or reducing public sector employment. While these policies might align with donor ideologies, they often disregard the specific needs and contexts of recipient nations, undermining their autonomy and the democratic will of their people.

In the 1800s, colonial powers used guns, ships, and soldiers to seize control of Africa. Today, the tools have changed, but the intent remains strikingly similar. Predatory loans and grants, often laden with exploitative terms, have become the modern mechanisms of control. Aid, when used this way, is not a gift but a strategic instrument of neocolonialism, designed to maintain influence and economic dominance over African nations.

Economic Dependency: The Hidden Cost of Aid

Foreign aid often arrives with promises of development, yet it can inadvertently foster economic dependency. Many recipient nations come to rely on consistent inflows of external funding to balance budgets, finance public projects, or even meet basic needs. This dependency discourages governments from seeking sustainable, homegrown solutions to economic challenges. Over time, aid dependency erodes the incentive to develop resilient local industries or invest in revenue-generating sectors such as agriculture, manufacturing, and trade.

The result is a vicious cycle: nations trapped in a perpetual state of reliance on external assistance, unable to achieve true financial independence. The stagnation of local economic innovation and entrepreneurship becomes a direct consequence of this reliance. Aid donors, meanwhile, gain leverage over the policy and fiscal decisions of recipient governments, further entrenching the imbalance of power. Without a shift toward self-sufficiency, the long-term economic health of these nations remains precarious.

Aid Effectiveness and Waste: When Good Intentions Miss the Mark

Aid programs are often plagued by inefficiencies and mismanagement, leading to outcomes far removed from their intended goals. Funds earmarked for essential services such as healthcare, education, or infrastructure are frequently lost to bureaucratic overheads, poorly designed projects, or corruption. In some cases, donor nations push for high-visibility projects that serve their public relations agendas but have minimal impact on local communities.

Even when projects are well-intentioned, they often fail due to a lack of alignment with local needs or conditions. For instance, the construction of roads or hospitals may fall short without plans for maintenance or operational sustainability. Aid recipients, particularly in rural areas, are left with unusable infrastructure or services that cannot be sustained. Such waste underscores the need for greater accountability and collaboration in designing and implementing aid programs.

Distortion of Local Economies: The Market Fallout

Aid can inadvertently disrupt local economies by introducing external goods and services that undermine domestic industries. The donation of food aid, for example, often floods local markets with free or heavily subsidized imports, leaving local farmers unable to compete. Similarly, foreign aid tied to specific donor-country contractors or suppliers can exclude local businesses from participating in lucrative projects, stifling their growth.

This market distortion discourages the development of local production capabilities and creates a dependency on external goods and expertise. Over time, it hollows out domestic economic resilience, leaving recipient nations more vulnerable to external shocks. Effective aid programs must prioritize building local capacity and supporting industries that contribute to long-term economic growth.

Cultural and Social Impacts: Erosion of Local Identity

Aid programs often come with an implicit imposition of foreign values and systems, leading to a disconnection between the intended goals of development and the realities of local communities. Western ideals embedded in education, governance, or health initiatives may clash with indigenous practices and traditions. This imposition can marginalize local knowledge and solutions, fostering a sense of alienation among the people aid is supposed to help.

Moreover, the dependency fostered by aid can shift societal dynamics, creating hierarchies based on proximity to foreign funding or decision-making. Communities may become more focused on catering to donor expectations than addressing their own priorities. Respecting and integrating local cultural contexts is essential to ensuring that aid efforts empower rather than displace local communities.

The Role of NGOs and Donor Agencies: Accountability Under Scrutiny

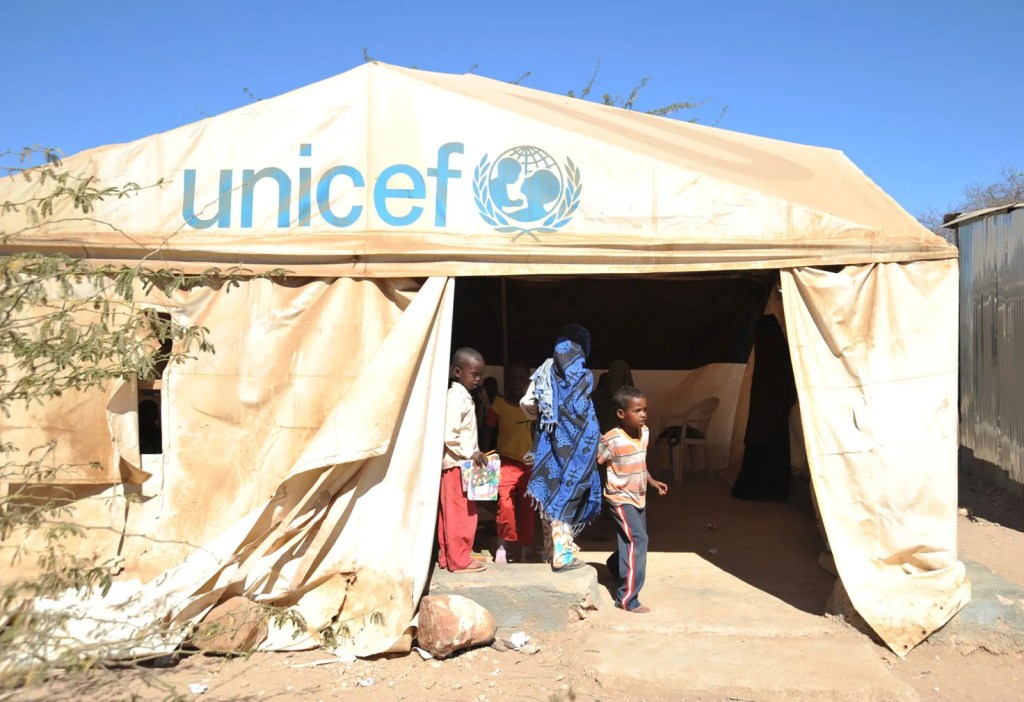

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and donor agencies play a significant role in distributing aid, but their operations are not without criticism. Many NGOs operate with limited accountability, leading to questions about how funds are spent and whether their efforts align with the long-term development goals of recipient nations. Donor agencies, meanwhile, are often influenced by the political and economic agendas of their home countries, prioritizing projects that serve their interests rather than those of the communities they aim to help.

Additionally, the presence of foreign NGOs can overshadow local civil society organizations, diverting resources and talent away from grassroots initiatives. For aid to be truly effective, it must support the growth of local institutions, ensuring that communities have the capacity to sustain development independently of external actors.

Long-term Environmental Consequences: An Overlooked Cost

Aid-driven development projects often overlook their environmental impacts, leading to unintended consequences for recipient nations. Infrastructure projects, such as roads, dams, or urban expansions, frequently disrupt ecosystems and displace communities without adequate mitigation plans. Similarly, agricultural aid programs that prioritize monoculture or high-yield crops can deplete soil fertility and exacerbate water scarcity.

The environmental costs of such projects are often borne disproportionately by the poorest and most vulnerable communities. Sustainable aid practices must prioritize environmental resilience, integrating conservation and renewable energy solutions into development initiatives. By addressing these long-term consequences, aid programs can better align with the holistic needs of recipient nations.

Alternatives to Traditional Aid: A Path Forward

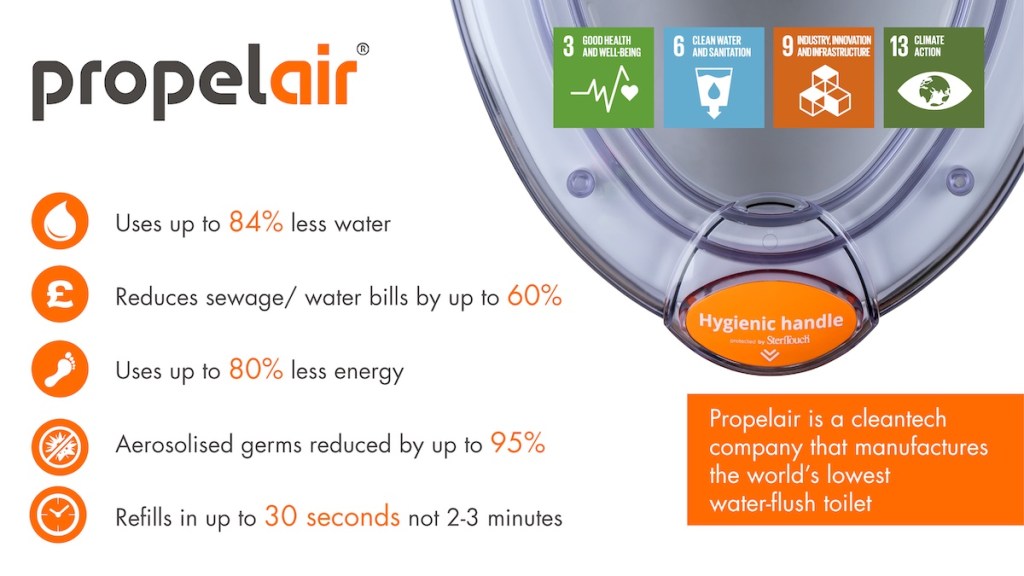

Rather than relying on traditional aid, fostering trade and investment may provide a more sustainable path for development. Encouraging regional trade partnerships and reducing barriers to market access can empower nations to grow their economies organically. Initiatives that prioritize skills transfer, entrepreneurship, and technology adoption can help create jobs and build local industries.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) and public-private partnerships offer another avenue for sustainable development. Unlike aid, FDI often brings with it long-term commitments to local economies, including job creation and infrastructure development. By shifting the focus from aid to economic collaboration, nations can reduce dependency and build a future rooted in self-reliance and mutual prosperity.

Be Critical: A call to action

To quote American political scientist, adviser and academic (ironically), “The West won the world not by the superiority of its ideas or values or religion… but rather by its superiority in applying organized violence. Westerners often forget this fact; non-westerners never do.”

They can no longer stab, shoot or kill us so their guns come wrapped in white envelopes and their knives signed by their treasurers. Be Critical, there is no such thing as a free meal.