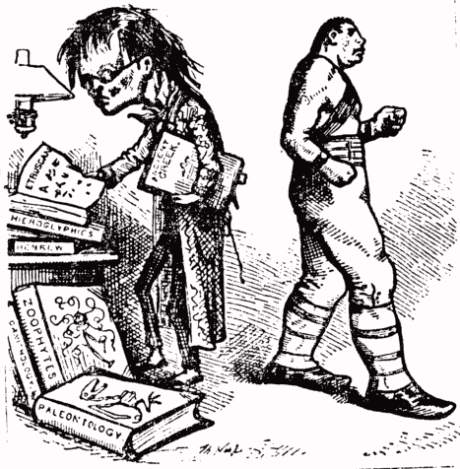

The title of our conversation is a bit of a mouthful, so let’s start with some context. Those familiar with philosophical reasoning will recognize the satirical nature of our title—a direct contrast to the term “Razor.”

To be fair, that does not help much, because what on earth even is a “Razor”?

In philosophy, a razor is a principle or rule of thumb that allows one to eliminate unlikely explanations for a phenomenon or avoid unnecessary actions. At least, that is what Wikipedia says. Well then, what is Alder’s Razor? Alder’s Razor (also known as Newton’s Flaming Laser Sword) states: “If something cannot be settled by experiment or observation, then it is not worthy of debate.” In simple terms, do not waste time on philosophical debates that cannot be settled. Stick to solutions with real-world impact. A little cheeky of Alder to take a jab at philosophers like that.

Given that little bit of context, why is this line of thinking problematic? What is the purpose, if any, of our resistance to intuitively good advice? Well, that is what we are here to explore.

The Paradox of Alder’s Razor

If we reject untestable claims outright, doesn’t that make Alder’s Razor itself meaningless? How do we “test” its validity? What foundational truth do we have that reinforces the notion that philosophical conversations carry no intrinsic value in the fruitful progression of society?

In addition to its self-contradiction, this principle is too rigid in its structure—too black-and-white to be applicable in a world full of chaotic discussions around law, social justice, and liberation.

It is reminiscent of the teachings of German Philosopher, Immanuel Kant. His philosophy was one set in stone; he argued that morality was absolute regardless of context. Lying to someone, irrespective of the situation, is unjust, as it robs them of the autonomy that forms the foundation of who we are as humans—creatures with agency and free will. However, if a known murderer were to ask you where your wife and kids are, would it be moral to speak truthfully?

Lines of reasoning similar to Kant’s carry one critical fault: they assume benevolence in the actions of all those we share our space with. They disregard the nuance and gray areas that come with navigating the maze of life, and as we know, ambiguity is a critical part of the human experience.

Mike Alder made a very similar mistake when coining his famous ideology. He assumed that philosophy exists in a vacuum—another reflection of his oversight regarding the interconnectedness of our world.

The Case for “Useless” Debate

The fact of the matter is, philosophical debates that seem “unsettleable” often shape scientific and social progress. Ethics, metaphysics, and epistemology—all essential fields—would be discarded if we applied Alder’s Razor strictly. Many scientific principles began as untestable philosophical inquiries (e.g., atoms in ancient Greece, heliocentrism before telescopes).

Some of the most prolific scientists of modern history often dabbled as philosophers themselves. They understood the importance of intellectualism in the pursuit of knowledge—knowledge that would later inform the very same practical solutions that Mike Alder places such heavy emphasis on.

Innovation is not just a switch you can flick to start manufacturing talking cell phones and flying cars—it’s a process. A process that begins (every single time) with curiosity and philosophical inquiry.

A famous (and ironic) example of this process at play is Isaac Newton’s discovery of the gravitational laws of motion. Before Newton formulated his laws of motion and universal gravitation, philosophers and scientists debated why objects fell and how celestial bodies moved. Why is this ironic? Well, another name for Alder’s Razor happens to be Newton’s Flaming Sword.

Prior to his theory and writings, we had contributions from brilliant minds like Aristotle, who proposed that objects fall because they seek their “natural place.” Kepler and Galileo also had a few ideas about why things move the way they do. Up until Newton’s theories were proposed and later proven, the topic of gravity was purely philosophical—effectively worthless and inconsequential to the lives of everyday historic citizens. Those very same “worthless” ideas went on to shape how we perceive the entire discipline of physics and even its younger brother, engineering, as we know them.

The philosophy of consciousness has not been “settled” experimentally, yet it influences AI, neuroscience, and ethics—all of which are critical to the advancement of technology and real-world solutions. Alder was not having a great day in the office with this one.

The Role of Thought Experiments and Philosophy

Philosophy often advances knowledge through thought experiments rather than physical experimentation. Schrödinger’s Cat, the Trolley Problem, the Ship of Theseus—without engaging with abstract thought, would we ever develop meaningful ethical frameworks?

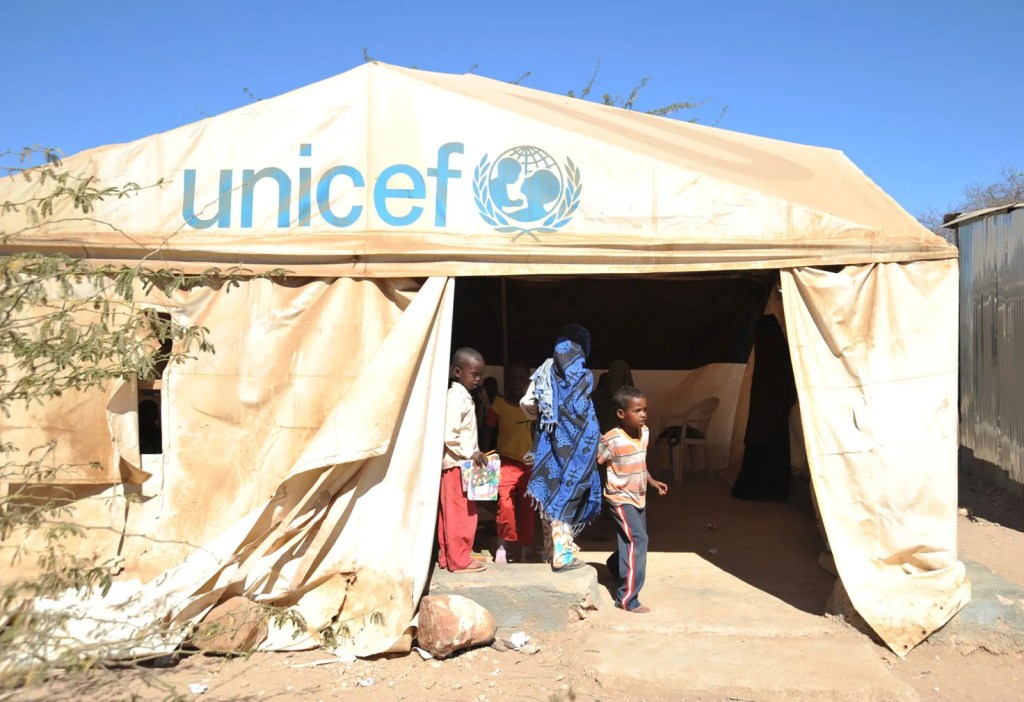

Ideas like 17th-century liberalism and the Enlightenment, spearheaded by thinkers like John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Montesquieu, inspired democratic revolutions (e.g., the American and French Revolutions) and later shaped human rights frameworks. These ideas laid the groundwork for leaders like Nelson Mandela, Steve Biko, and Oliver Tambo in their fight and eventual triumph against the Apartheid regime. Our defiance just became a little more intuitive. The only viable way to argue in favor of liberation and human rights is through philosophical thought. In advocating for autonomy, dignity, and freedom, it is critical to speak on the philosophy of ethics, agency, and law.

Abolitionism and human dignity allowed anti-apartheid activists to draw parallels between slavery and racial discrimination in South Africa. Philosophies like Marxism and anti-colonial thought held strong influences in liberation movements like the ANC and PAC.

These philosophies, often dismissed as “just ideas” at their inception, eventually shaped some of history’s most significant movements for justice. If we followed Alder’s Razor and rejected such philosophical debates as impractical, would these revolutions have ever happened?

Alder’s Razor as an Excuse for Anti-Intellectualism

The dismissal of complex discussions in favor of “practical” answers can be an excuse to avoid deeper thinking. Positivist movements rejected metaphysics, only for it to resurface in new forms. Does this mindset encourage oversimplification in an era that needs critical thought more than ever?

The fact that Alder’s Razor is very often invoked as a Hail Mary attempt at evading critical philosophical thought, even in modern times, does not exactly help its case. The fact of the matter is, we need to call it what it is—a backdoor. An Irish goodbye from a party filled with brilliant minds curious about the mechanisms that govern our society. A reluctance to pursue knowledge, regardless of the justification, is an act of cowardice. A refusal to destroy the very principles that have influenced our thinking for our whole lives in favor of newer, potentially more robust ideas.

A Defiance of Philosophical Criticism

For centuries, abstract thought has influenced the way we perceive ourselves and each other. Philosophy not only serves as an inquiry into our world but as a tool for introspection. Our ideas influence who we are, how we behave, and how we think at an individual level. Society, by definition, is a collection of individuals—each member serving as a critical component of the machine, a brick in the wall that shields us from anarchy. Thus, if we can change how an individual thinks, we can change how a nation thinks.

Philosophy has, and continues to, inform policy, ethics, human rights, and even the vocabulary we choose to use in business meetings and on dates with the girl from the coffee shop. Not only is it critical to the process of creating real-world solutions, but it is also inherent to the way our minds are wired. The ability to think abstractly, to dream wildly, and to fantasize about a reality not yet born—that is what makes us human. And if history is indeed a reliable storyteller, it is also what initiates progress.

The next time you are considering having a “worthless” conversation about the chicken and the egg or venting about your existential crisis to a friend, do it. What you may see as worthless now may well become the foundational basis of the society we build for our children.